Western art typically distinguishes between portraiture and figure drawing. The model-artist relationship would benefit greatly – for justice, for purity, for respect, for human understanding, for common sense, and for better art – by being brought closer to the artist-sitter relationship, or better, by being fundamentally a human relationship which has production of art work together as part of its goal.

There are three basic expressions used in schools for a particular kind of artwork. The expressions are “figure drawing”, “drawing from life” and “drawing from the model”. Any of these terms can be used to describe one of two fundamental ways of approaching human beings as subjects of art work. The other of the two ways is “portraiture”. In portraiture, artists work to express the character – real or supposed – of their “sitters”. In figure drawing, painting, or sculpture, artists work to depict what art critic Grace Glueck has called “the elusive human body of the model.”

There are three basic expressions used in schools for a particular kind of artwork. The expressions are “figure drawing”, “drawing from life” and “drawing from the model”. Any of these terms can be used to describe one of two fundamental ways of approaching human beings as subjects of art work. The other of the two ways is “portraiture”. In portraiture, artists work to express the character – real or supposed – of their “sitters”. In figure drawing, painting, or sculpture, artists work to depict what art critic Grace Glueck has called “the elusive human body of the model.”

There are several differences between a model and a sitter in relation to an artist. First, and almost most obvious, usually the sitter pays the artist, while the artist pays the model. Second, the resulting art work stresses character in the portrait and form in the figure drawing. Third, the work of art that results in portraiture belongs to the sitter, while the work that results in figure drawing belongs to the artist. Fourth, figure drawing sessions usually result in “sketches” which may be used in some way later for something more major, while the portrait is the major work for which the sitter is sitting. Fifth, the portrait is usually partial, featuring face and, in recent centuries, hands, while figure work is usually full-figure, with attention to extremities – often including face-reduced.  Finally, and perhaps most obvious, a sitter is usually clothed, and a model is usually (though not always) naked.

Finally, and perhaps most obvious, a sitter is usually clothed, and a model is usually (though not always) naked.

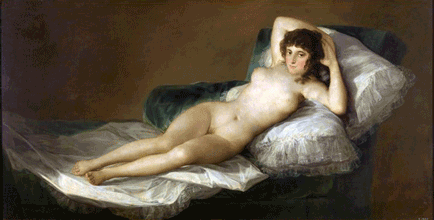

Two paintings which point up the most obvious distinction between sitter and model, by challenging it, are Francisco Goya’s “Maja Clothed” (Maja Vestida) and “Maja Nude” (Maja Desnudo). Both are portraits of the same person in almost the same pose. The nude version is as detailed and personal as the clothed version (though there are surprisingly meaningful variations, such as an apparent absence of make-up and of bed covers in the nude version), and the nude portrait becomes allowable in standard society because it mirrors a clothed version.  The existence of both shows society that a dichotomy between how artists treat people with clothes and people without them is, to speak gently, artificial.

The existence of both shows society that a dichotomy between how artists treat people with clothes and people without them is, to speak gently, artificial.

This very artificiality is the point of the dichotomy. Portraiture comes as close to some apparent reality as possible; a figure, clothed or naked, is presented for reasons apart from the people involved in the work: you are meant to look at the picture. That is why illustrations for fictional work are usually figurative, most clearly exemplified by illustrated children’s stories. Portraits (except in the case of biographies), would bring in substance extraneous to the ideas in the text.

Western society has an interesting tradition of combining figure bodies with portrait heads. Standard practice in ancient Greece, and then in Rome, demanded that people (almost always, men) be depicted as though their bodies were ideal, but the head was rendered as a portrait. It was these likenesses that the vandals most thoroughly “vandalized” as a symbol that power no longer belonged to the people portrayed.

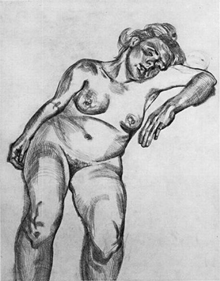

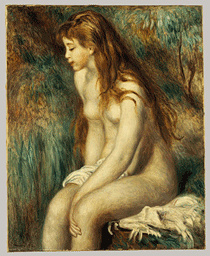

Portrait bodies, recognizable as such, don’t make people comfortable. Perhaps the best-known “scandalous” examples of this sort are several sculpted nude versions of Honoré de Balzac by Auguste Rodin. Human bodies are ordinarily presented in a way which idealizes them, thus encouraging us to pass over their reality and its various meanings, including sexual meanings. This idealization continued with few exceptions throughout the history of Western art. Exceptions are important: they include the nudes of Rembrandt and Dürer, among others. Painters such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci seem to have modified portraits in a figurative direction. Renoir found lovely “figures” to portray, among them his Young Girl Bathing in the Metropolitan Museum Collection.

Portrait bodies, recognizable as such, don’t make people comfortable. Perhaps the best-known “scandalous” examples of this sort are several sculpted nude versions of Honoré de Balzac by Auguste Rodin. Human bodies are ordinarily presented in a way which idealizes them, thus encouraging us to pass over their reality and its various meanings, including sexual meanings. This idealization continued with few exceptions throughout the history of Western art. Exceptions are important: they include the nudes of Rembrandt and Dürer, among others. Painters such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci seem to have modified portraits in a figurative direction. Renoir found lovely “figures” to portray, among them his Young Girl Bathing in the Metropolitan Museum Collection.

Idealization is ambivalent. It allows both affirming reactions and negating reactions, in a way that frees people from responsibility. This freedom from responsibility is key to development of such a deep dichotomy, in ordinary artistic practice, between the portrait and the nude.

This categorization, however, is often confounded by individual art works. A portrait beyond portraiture, for example, is Hans Holbein’s Sir Thomas More.  In this example, the universality beyond individual character was in the subject of the portrait, but it took a portraitist like Holbein to find and present it. Rembrandt’s portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels as Bathsheba at Her Bath brings portraiture and figure work into unity, while transcending both.

In this example, the universality beyond individual character was in the subject of the portrait, but it took a portraitist like Holbein to find and present it. Rembrandt’s portrait of Hendrickje Stoffels as Bathsheba at Her Bath brings portraiture and figure work into unity, while transcending both.

People do recognize a basic connectivity in all aspects of life. Because of this, there is deep concern to keep relationships between artists and models idealistic from the beginning, so that “due separation” will be maintained under every circumstance. If the relationship between these two people is allowed to become personal, it might well become sexual. There are plenty of historical examples in which this has happened, and people are rightly worried that a “tainted relationship”, passing into an art work, might taint those who receive it. This question needs an answer. Many people feel that it is the nude which, at its best, is our greatest art: we want to assure ethical safety in making and appreciating nudes.

The standard solution is to “keep sex out.” But we are neither whole nor truly nude when sexuality is somehow excised from us. A second solution often proposed is to “keep the relationship professional.” This last is the same as the first, but it is more complicated, has far-reaching social complications, and needs a complicated answer.

The standard solution is to “keep sex out.” But we are neither whole nor truly nude when sexuality is somehow excised from us. A second solution often proposed is to “keep the relationship professional.” This last is the same as the first, but it is more complicated, has far-reaching social complications, and needs a complicated answer.

Supposition that a relationship between an artist and a model must either be professional or be sexual involves a set of presumptions that diminish art and turn out to be rather insulting to people as artists and, especially, to people as models.

People presume that the presence or avoidance of intimate relationship is the key to defining the two different artist-model relationships. To avoid identification with a model in a sexual way, artists have often withheld personhood from figures in their works. For much of Western history, genitals other than those of prepubescent boys have been hidden, diminished, cut out or overlooked in finished works of art.

The second presumption is that modeling is demeaning. It is seen as an activity outside a person’s real goals, unless that person is a “career” model posing at art schools for a meager living. In fact, modeling can be a valid performing art, worthy of the same respect as other performing arts. It demands projecting to the artist: performing artists know this projecting is important, and can provide it.

Life drawing classes or workshops often have as their focus the depiction of the (admittedly, elusive) human body. Reduction of person to body is demeaning. Models are doing the artist the honor of entrusting themselves: for love, for money, for practice, for whatever human reason or combination of reasons brings them.

Life drawing classes or workshops often have as their focus the depiction of the (admittedly, elusive) human body. Reduction of person to body is demeaning. Models are doing the artist the honor of entrusting themselves: for love, for money, for practice, for whatever human reason or combination of reasons brings them.

Finally, it’s presumed that professional interest should be less than personal. Professional is a word with various grades of meaning. It can mean extraordinary skill, gained through education and enhanced through experience, performing a humanly valuable function which requires such skill: from doctors, to teachers to mechanics. Sometimes skill needs exercise without the truly human framework where it belongs: it would not be practical for a doctor to become friends with every patient. Where this is recognized by both doctor and patient, it is appropriate. A human relationship cannot be truly human unless it is equal: superiority-inferiority has no place. For artists and models, the two types of relationship—impersonally professional or intimately sexual—are both one-sided. Instead, both model and artist can give as much as they feel appropriate in the situation, and take as much as seems right to them, in agreement with each other.

Alleged “professionalism” does not provide the protection against corruption which it first seems to offer. Pablo Picasso is well-known as someone who had sexual experience with people who worked with him as models, and also as an artist who did not only nudes, but erotic art. This art is often delightful, and need not be arousing except through personal effort on the part of the viewer. As St. Paul notes, “to the pure, all things are pure.” There are complications, but the complications belong.

Alleged “professionalism” does not provide the protection against corruption which it first seems to offer. Pablo Picasso is well-known as someone who had sexual experience with people who worked with him as models, and also as an artist who did not only nudes, but erotic art. This art is often delightful, and need not be arousing except through personal effort on the part of the viewer. As St. Paul notes, “to the pure, all things are pure.” There are complications, but the complications belong.

Prudence always has a place. This applies to our abandon, which is the ultimately valid attitude to any work of art. There has to be a special kind of value in something, so that I may allow it to overwhelm me: let it transform me, so that I have become different because of it.  Abandon sometimes has to be careful and gradual, rather than immediate; but it can become complete, in time, as a work shows itself worthy of abandon.

Abandon sometimes has to be careful and gradual, rather than immediate; but it can become complete, in time, as a work shows itself worthy of abandon.

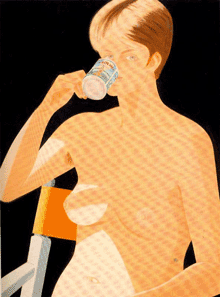

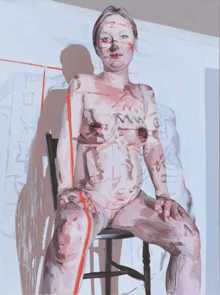

This article was begun in the 1980s, and my brother Nicholas suggested that I update it with reference to some contemporary artists.  Nude portraits by Lucian Freud, Alex Katz, Alice Neel and Jenny Saville are included here. These painters taught me other ways of doing things right, and remind me that human perception, understanding and expression, at its best, remains individual and personal.

Nude portraits by Lucian Freud, Alex Katz, Alice Neel and Jenny Saville are included here. These painters taught me other ways of doing things right, and remind me that human perception, understanding and expression, at its best, remains individual and personal.

A given wisdom that insists that nudity be presented or received on an artistic level only in an impersonal way fosters continued separation of humankind from human sexuality and human sexual behavior, as well as anything else in personality that is fully human. The relationship between the person who is a model and the person who is an artist embodies all the possibilities of change, development and dissolution that other specifically human relationships embody, and needs the same kind of care in order to be fruitful. That includes care that sex remains in its appropriate place within the context of the full relationship. Everything belongs in context: it is isolation that does damage. Sex belongs from the beginning because it is there. It is part of any relationship between people mutually attractable to each other, unless they have blinded themselves to the attraction: a blindness deadly to art. Attraction, awe, fun, prudence, love and delight are surely part of the explanation of why people like to look at art work involving nudes, and why many people like to be involved directly, as artists, as models, or as both, in this work.

There is a rather sexist saying attributed to Renoir which, in some way, is more deeply right than it is wrong. To him, a nude was not finished until he was ready to pat her on the bottom. There is a sense of tenderness here, and of real play: real play is relevant, and reverent.

The Greeks told an admiring joke about their sculptor, Praxiteles. When he had finished his great sculpture of Aphrodite, the goddess appeared to him and said, “Oh Praxiteles, wherever did you see me naked?” What Praxiteles had done was not a figure, it was a portrait.

William Blake, in one of his poems, offers a model of how to approach figurative art, whether as model, artist, sitter or recipient:

To Mercy, Pity, Peace and Love all pray in their distress

And to these virtues of delight return their thankfulness..

For mercy has a human heart, Pity a human face,

And love the human form divine, and peace the human dress.

1. Artist and Model:Why the Tradition Endures,”NewYorkTimes,June8,1986

2. www.museodelprado.es

3. www.museodelprado.es

4. www.philamuseum.org/collections

5. www.metmuseum.org/collections

6. http://www.frick.org

7. www.louvre.fr

8. Picasso,“Nude with Joined Hands”

9. Picasso, “Faun Revealing a Sleeping Woman”

10. Lucian Freud,“Blond Girl”

11. Lucian Freud,“Man Posing”

12. Alex Katz,“Morning Nude”

13. Alice Neel,“SelfPortrait”

14. Jenny Saville, Isis, 2011